February 28th, 2021. I have just finished five and a half months of chemotherapy. Next week, I start five days of radiotherapy. The end is in sight though, as time passes, I will come to understand that, when you have had cancer, there is never really an end. You will always have to push down the feeling that, at any point in the near or distant future, it might come back and snatch away your life. This is the bad bit. The good bit is that it makes you appreciate every day. It makes you grateful for the people you have in your life.

2020 was not a normal year for anyone. Mine is just another story. A cancer diagnosis in July. Surgery in August. A move north in September. A start to treatment in October. The work I was due to start as an RLF* fellow has to be postponed. I cannot find solace in writing. I can’t think straight enough to put pen to paper or open my laptop. I can’t even read. And because I have to shield, all I can manage is a brief walk each day, not enough to blow away the cobwebs.

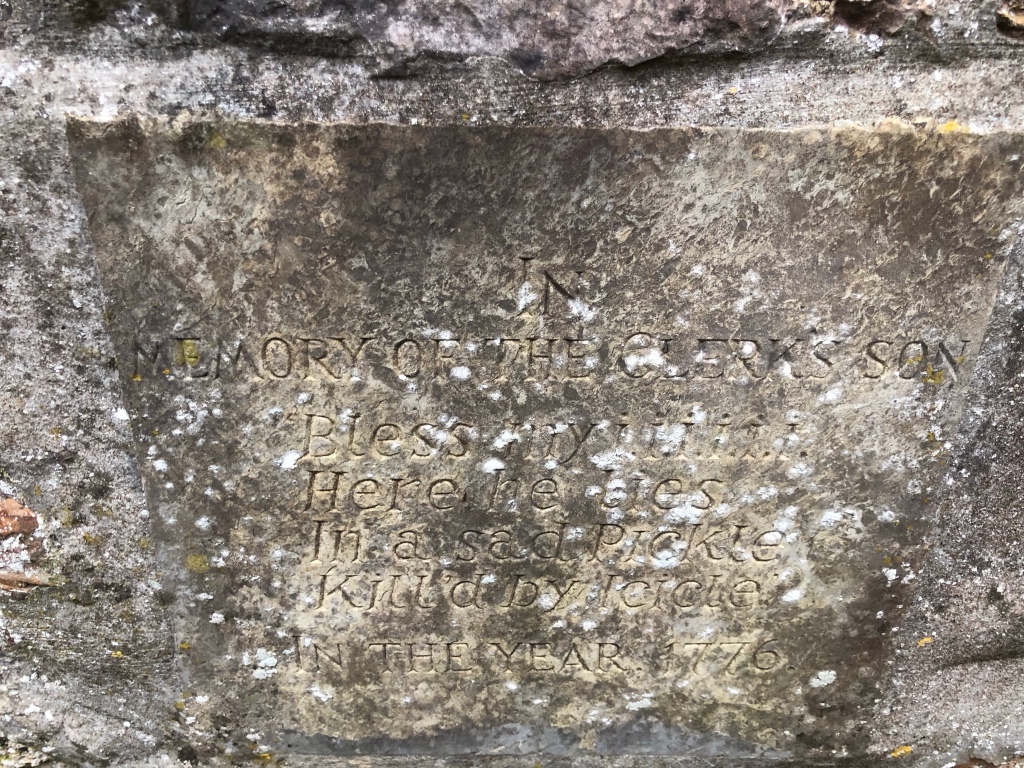

Eventually, as things open up in spring 2021, thanks to a family legacy, I buy a caravan in the Marches, an escape to the country where I discover the churches of Shropshire. Each one a little gem full of history, art, genealogy and stone floors worn down by a thousand years of worshippers and church crawlers like me. I become a tombstone tourist. A taphophile. And, as I face an uncertain future, I find like-minded people on Twitter, experts in their fields and I begin to learn about memory, memorialisation, and mortality. My interest in death, which has been simmering since I was two years old when I saw my first dead body, is now full steam ahead. And, when I finally take up my post at the University of Manchester, a year later than originally planned, I am inspired by the young history students and start writing again – this time non-fiction. Narrative non-fiction crossed with memoir.

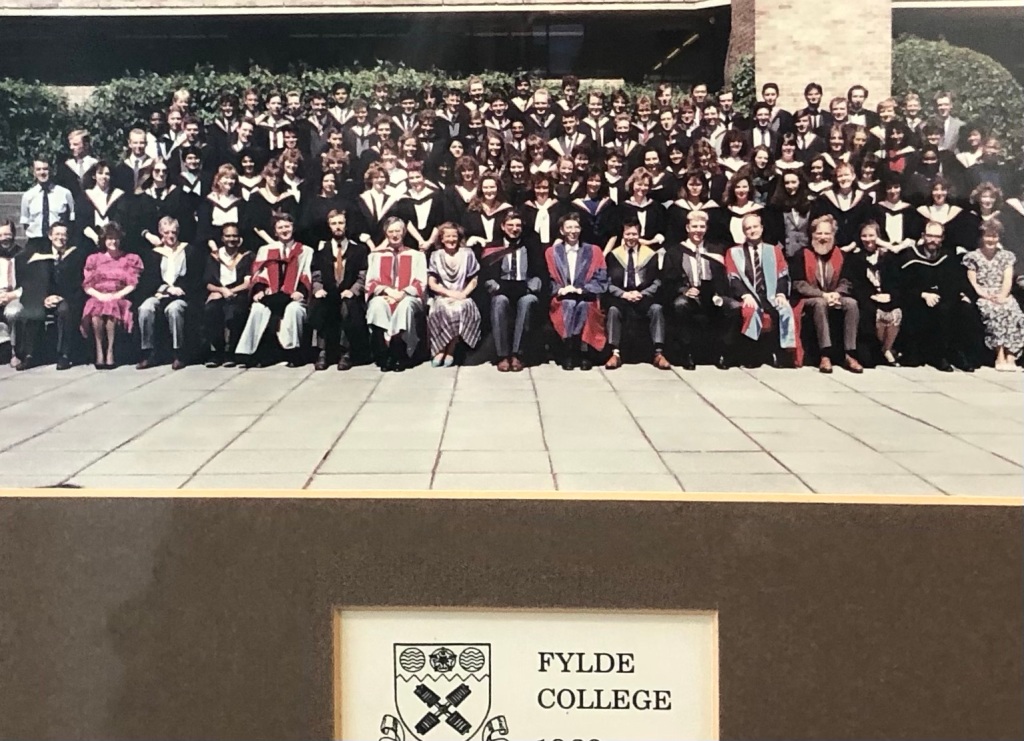

Exeter, the Wirral, Manchester, Shropshire, what have these got to do with Lancaster? Well, they are all places that have played a role in my life but perhaps Lancaster had the most significant part. It is where I met my ex-husband. Where I made my best friends. Where I became sort-of-friends with my partner. Where we sat next to each other at graduation, our surnames alphabetically neighbours. I didn’t see him again for nearly three decades but when we met up at a reunion, we became friends. And when we both found ourselves separated, we became more than friends. And when Covid and cancer struck, I moved to be with him. So we decide to return to Lancaster. Actually, I instigate the return. A trip down memory lane. Research into my book. He is used to being taken round churches and graveyards, hunting down memorials and stories about death. As you will know if you read Part I, Lancaster is rich pickings.

February 29th, 2024. Leap Day. There is an Irish tradition (something to do with St Bridget and St Patrick) where the woman asks the man to marry her. This is my plan. I will do the romantic thing. We spend the day out and about in Morecambe and Lancaster. As the hours pass, my nerves grow and I am unsure how or why – or even if – I will do this.

(And for this next part, I need to explain something about the collegiate system of Lancaster University. Established in the 1960s, alongside York, these two universities were supposed to be the Oxbridge of the North. Once offered a place, you would be allocated a college with its own residence blocks, JCR and bar. I was given Fylde. This was where we would congregate day in, day out, over the next three years. This was our home. The other Fylde students our family. I think this is why I have such solid, long-standing friendships from that time. An important time. A coming-of-age time.)

In the afternoon, we drive out of the city and up to Bailrigg, check into guest accommodation. Then we do our own tour, knowing things will be different, knowing our old blocks have been replaced with new ones – ensuite rooms with wifi – hoping to see something of the place that played such an important part in our lives. As we stumble across campus, we pick out some old haunts obscured by the changed landscape. But we must look lost because an older bloke stops us, asking if we need directions. We tell him we’re graduates and it turns out he started as a lecturer here in 1990, the year after we left. Now, in 2024, this is his last year before retirement. He asks which college. (Always the first question.) When we tell him Fylde, he looks pleased as this is one of the least changed colleges, with the best bar. Gone are the days when students drank, he tells us. They are too serious now. Though they might dabble in drugs, they are not the booze hounds we were. After a long chat – bands in the Great Hall, fees, the collegiate system – he reluctantly lets us go, after harking back to the days when lecturers would go to the long since departed Ash bar on a Friday afternoon. And I remember a tutor who once offered to tell me the exam questions if I bought him a pint, relieved I had the moral wherewithal to say no.

We head to Fylde as the night draws in. We drink our pints, working out where we would have sat back in the day. The old bar has gone, the new one incorporated into the JCR so it is one large open plan space. It’s disorientating but, after a while, we can see through the shiny new to the grubby old. We can picture our friends, dressed in Levi’s and slogan T-shirts, lounging round eating buttery toast served through a hatch by a woman called Jackie. Ron and his wife Marg, the landlords, pouring pints with weary expressions at these bloody students. The porter crossing the quad, off to bust a noisy party in one of the blocks. Friends who grew up to become high-ranking civil servants, politicians, social workers, teachers, accountants, business people, executive producers. We grew up. But, being back here, Neil and I are briefly young again.

After he has yearned for the old pool table and dartboard rather than the spanking new ones, he heads to the loo. This is my chance. I dash to the bar and ask the student bartender if ‘Echo Beach’ is still the Fylde anthem. She looks blank. ‘Echo Beach’ by Martha and the Muffins. She has never heard of it. I am about to ask where the juke box is but am spared the embarrassment when she tells me they have Spotify on an iPad and she can play it if I want. So I divulge my plan. She is excited, tells me to give her the thumbs up when I am ready. A minute later, Neil is striding back across the room and, at the signal, ‘Echo Beach’ rings out across the years. I gesture him over. He looks sheepish. I reckon he knows what I am up to. As he reaches me, I get down on one knee and take the lid off the small box that has been hidden in my bag all day. Inside is a ring. A Haribo ring. Will you marry me, I ask. He smiles. I suppose I better had, he says. Once I have squeezed the ring onto this finger, there is an outbreak of applause from the room, young people wondering what on earth these old folk are doing in their space, but humouring us all the same.

I am grateful for this day. I am grateful for the people I have in my life. People I would never have met if I had got the grades to go to my first choice university. Leeds night be a great city, but Lancaster made me.

- The Royal Literary Fund (RLF) is the writers’ charity who have been there for writers in need since 1790.